Too little information means you’re less likely to get the results you imagined.

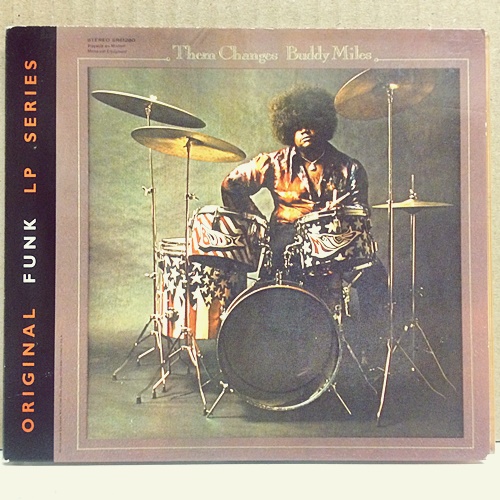

#Them changes lead sheet software

I print and look for problems, as well as listen to the software play it down. Once the tune is input into the notation program it’s time to fine tune the layout. Creating a separate solo section creates more breathing room for soloist and rhythm section. This puts players at ease, especially when sight-reading the chart. But when the arrangement gets complex, a section of solo changes removes questions about the solo form. If possible I go with a lead sheet that’s clear enough to solo over. My compromise was to compose the chart then hide the empty staves at the end. This allowed me to put in rhythmic figures, voicings and bass lines where necessary. Hiding empty measures removed excess space that bloats page count. This is my go-to form, but there’s a caveat: you end up with twice the page length. But what about when you have specific voicings or bass lines? If you remove those parts, it might be a shadow of the composition you created. This eliminates questions like “Do we take the first ending on the repeat?” Step 3: choose a layoutĪ basic, one staff layout works for a lead sheet with only a melody and chords. In the end, I chose more duplicate sections and fewer repeats. But I had to weigh how much extra mental stress that adds for a player reading the chart.

There are several parts in this song where 2 or 4 measure phrases repeat several times. This helped me find the simplest roadmap. Once I could visualize the chunks, I could plan a better roadmap. Much faster than moving sections around on staff paper or in a notation program. This allowed me to play with their position and find the optimal grouping. To help see what was going on, I wrote each section on an index card and laid them on the floor. Condense as much as possible? (Result: confusing repeats ).Write everything out? (Result: long, redundant chart.).This presents a couple hurdles from an arrangement standpoint. The tune follows pop song form-verse, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, solos, verse, chorus, ending-instead of a traditional jazz scheme like 12, 16, or 32 bars. Charts can grow to unmanageable page lengths.įixing “Belief” Step 1: get an overview of the situation.(Voicings, rhythmic hits, that little line you want the guitarist to play.) It can be difficult to incorporate all the details.Everyone must be able to read (sight-transpose) from concert key.One chart to duplicate and bring to gigs (no ‘parts’ to manage).(No “Let’s take it again from letter ‘F’…umm, that’s measure 47 on your part.”) The entire band navigates from the same page.(Allows good drummers to interact better than reading empty measures with occasional rhythmic hits.) The biggest pros to a single lead sheet are: If I’m playing someone else’s compositions, it’s nice to have a Bb part.) (I rarely ‘read’ my own tunes on gigs, so they’re referential for me. They’re the most efficient way to communicate all the information to each band member. The downside is they often result in overwhelming multi-page charts. I prefer concert lead sheets whenever possible. This makes it difficult to (re)locate themselves at a glance. This gets complicated from both an organizational and performance standpoint. If the bass player and drummer are reading the bass part, they don’t see the melody. The bass part lacks the melody and the piano part is somewhere between the two. The 5-page score has lots of redundant information and is too hard to deal with on a gig.

Things appear more complicated than they are.

The downside is those recording charts don’t lend themselves to an easy read on a gig. The upside is I got exactly what I wanted on the recording. The original charts communicated details-specific piano voicings, bass lines-for the recording session. Challenge: Simplify a complex 5-page arrangement down to an easy-to-follow 3-page lead sheet. Problem: I never perform “Belief” because the chart needs too much explanation.Ĭan’t Wait for Perfect by Bob Reynolds Original 5 page chart for “Belief”. Maybe it will come in handy the next time you’re arranging a song. This is a detailed case study of why-and how-I spent two days reworking a chart. Balancing information on a page can mean the difference between a smooth performance and a train wreck. Creating charts for small jazz ensembles is an art form.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)